The Toyota Production System is not enough

It’s been tough several years for Toyota. The information gained from the Toyota website indicates that in 2013 alone (as of October), there have been almost 3.5 million vehicles recalled. Considering the total units produced in 2012 (the latest annual figures available) was 9.9 million; that’s an annual recall rate of over 1/3rd (35%) of vehicles produced. And this does not include the unknown number of vehicles involved in “service bulletins”, which are problems known to the company that require remedial action but do not warrant a formal recall. To give some perspective, if the average burdened cost to Toyota of the recall was only $100 per unit (a modest assumption, to be sure) the total cost of the recalls, so far, would be $350 million.

These are the kinds of numbers – and this is the kind of publicity – that should result in many sleepless nights for the leadership of Toyota and give cause for pause to the millions of disciples of the Toyota Production System (TPS) and the principles of Lean. Even the most fervent advocate of the TPS and Lean should be challenged to their core.

Certainly, with these outcomes, I would not want to emulate Toyota if I were a business leader (and I am) without a level of scepticism and some considerable due diligence. And I would be very distrustful and hesitant – even resistant – to embrace the approaches used by Toyota to improve the operations of my business blindly and out of faith, based only upon the past reputation of the TPS. After all, who wants to be known as, “the company that makes poor products, but does it very efficiently?” Hardly a path to sustainable viability or a rallying cry for converting customers into fans.

Of course, if we look at the nature of the recalls and their root causes, we find that almost none of the recalls are the result of actually manufacturing the components or assembling the final vehicle. Almost all of the recalls are the result of failures in product or production design and engineering. For instance (and to list just a few of the recalls);

- Oct 17: 803,000 vehicles recalled because water from the air conditioning condenser unit housing could leak onto the airbag control module and cause a short circuit.

- Aug 07: 342,000 vehicles are recalled because screws that attach the seat belt pre-tensioner to the seat belt retractor within the seat belt assembly for the driver and front passenger can become loose over time due to repeatedly and forcefully closing the access door.

- Apr 11: 170,000 vehicles are recalled because they are equipped with front passenger airbag inflators which could have been assembled with improperly manufactured propellant wafers.

I am sure some will scream, “See! It’s not the TPS or Lean that’s not working at Toyota! There are no defects in the manufacturing process. They are doing just fine!”

Sorry to disappoint those people – but in my opinion, Toyota is not doing just fine. There is a large part of the business that is operating at an entirely inadequate level of performance. And I will go even further and state that the general public does not recognize the “nuance” of who or what might be to blame the same way a zealot of the TPS does. All the general public sees, and rightfully so, is that the output and results of the efforts of Toyota are defective.

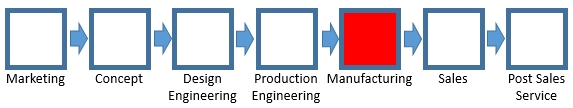

Most TPS and Lean professionals think of the production line as what goes on inside the factory (see red box below). And they believe that, if the intended output of their efforts is created with minimal waste and at peak proficiency, then they have accomplished their mission and accomplished it well. They might even consider the expansion of the TPS into any one of the other boxes. And from this “micro-level” perspective, that might be accurate.

However, if we examine the entire production line from a more “macro-level” perspective as illustrated above, starting with Marketing and going through to Post Sales Service – and including all of the Finance and Supply/Value Chain involvement points along the way – we can see that the actual production process, or any individual box, is but a small part of the overall process of delivering a vehicle to a consumer.

Given a basic tenant of the TPS and Lean is to rally resources when an opportunity for improvement is discovered, it stands to reason that a defect that is discovered at any point along this production line should result in an alert and that a Kaizen team be organized to resolve the defect before resuming the production process. If the problem exists in design or production engineering, it means that there probably has not been enough testing, or the right testing, or even an understanding of what needs to be tested and how.

Given this view, there are only two answers to the challenge. Either, i) the TPS is being grossly under-implemented – even at Toyota, or ii) the TPS is entirely inadequate as an enterprise-wide approach for attaining Operational Excellence and establishing the company as a High-Performance Organization.

If we consider the first, then the challenge is“How do we leverage the TPS to gain alignment and integration across the entirety of the enterprise?”Here, I believe it would be important to expand the nomenclature and toolsets of the TPS, even the name itself, so that it involves, incorporates and supports the entire company across all its aspects and endeavours.

And if we consider the second, then the challenge is “How do we design and deploy a business-wide operating system that integrates with the TPS for where it is appropriate?”In this case, a super-system for the entire enterprise would need to be developed and launched which seamlessly incorporates the TPS, leveraging the strengths of the TPS where such strengths might exist and augmenting the weaknesses of the TPS where appropriate.

The TPS was developed between 1948 and 1975, which makes it roughly 40 to 70 years old. And whilst it might have been transformational back in the day, it is obvious from the experiences and results at Toyota that the TPS is in dire need of transformation itself to remain effective and even relevant – and to meet the needs of the 21st Century organization. After all, even the TPS should be subject to Kaizen.

item 2 and 3 reveal a lack of application of FMEA in design and manufacturing at the sub system level,while item no:1 indicates an absence of System FMEA for assessing failure modes at subsystem interfaces.Cultural factors such as ” Not questioning” also play a part.

The necessity of involving the ultimate Customer in such situations,at an early stage may be foreign to automotive organizations,but may yield better results.

I’m curious to find out if you can share insight on any “Kaizen” on TPS. I would be really interested to learn about TPS version 2.0 , something that tells me that TPS needs to be Kaizen upon.

Vasu is correct. TPS did not cause or allow these defects. Although it is likely that not even NASA has a robust System FMEA process to assess failure modes of subsystems at a higher assembly level, these events clearly identifies the need for it in many organizations.

On my honest opion, this arcticle does not reflects the basics of understanding the Core or basic Toyota System. As I understand your article, you mix quality of materials with the production. Acording to the comments before: FMEA is for example a good module to get rid of some problems. I need to laugh, when I have to read that the Toyota System is “roughly 40 to 70 years old”. After all, Everybody who understands the basics of the Toyota thinking and the system has the right answer for the issues nowadays and in future.