Rethinking individual accountabilities on a Balanced Scorecard

Something I find a touch dysfunctional about designing and rolling out Balanced Scorecards is when it comes to the assigning of accountabilities. Standard practice is for individual managers to be assigned accountability for individual objectives, with aligned accountabilities for Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), etc.

Intuitively, this seems appropriate. After all, it’s a conventional belief that without clear accountabilities, work will not get done. But when applied to the Balanced Scorecard, there’s a particular challenge here – this is to do with cause and effect.

The challenge of cause and effect

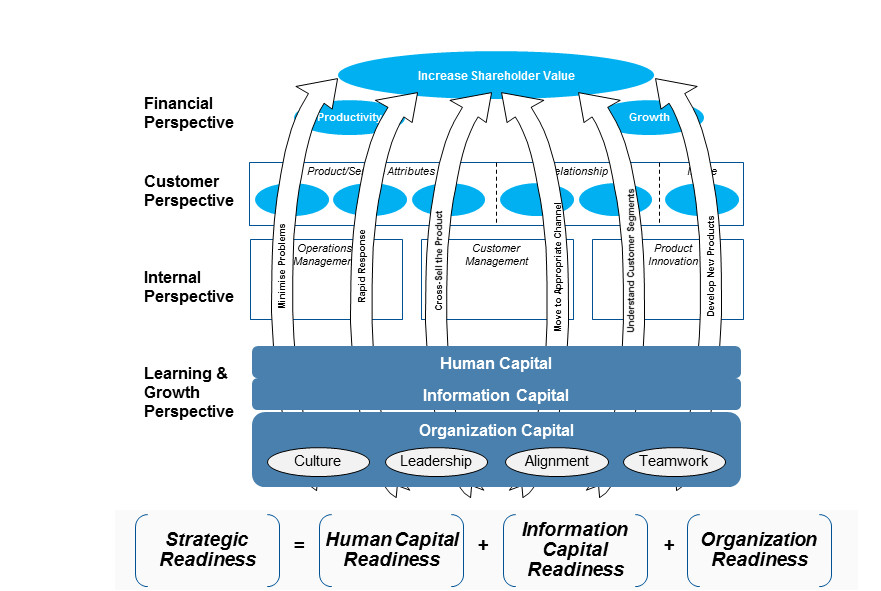

A central premise of the Balanced Scorecard system is that the capabilities we build in the learning & growth perspective enable the delivery of the strategic processes, which in turn deliver customer and financial outcomes. Cause and effect. Therefore objectives (and their supporting KPIs) are interdependent. No one objective delivers value in isolation and cannot be achieved without the input of others.

Consider outcome objectives. People can be given accountability for a financial or customer objective, but these are simply outcomes of the work done in the enabler perspectives (internal process and learning & growth). So, can a manager with say accountability for a Customer Experience objective be held accountable for the achievements of the managers of the driving enabler objectives?

Similarly, an owner of an internal process objective is dependent on the capabilities delivered by learning & growth objectives and oftentimes the performance of other internal process objectives. By the same token, the owner of a people-related objective such as High Performing Culture and supporting KPIs such as Employee Engagement (typically from HR) cannot possibly deliver to these without significant work by leadership and other managers.

Siloed approach to managing objectives

So, what typically happens is that accountable managers focus squarely on their own objective (typically fighting for the easiest targets against performance they can completely control) and ensure that the quarterly report for that objective is green. Job done. Cause and effect, or the relationships with other objectives, doesn’t register, or any best at a perfunctory level.

This problem is further compounded by the fact that accountability is usually assigned according to functions, so the objective is perceived as a reflection of the performance of that function. I was once told by a functional head that he would not accept a KPI target because he was worried it might be red, and that if so, he’d get fired due to his function under-performing. Not an uncommon response.

Conversely, a few years back, I worked with one department head in shaping a Strategy Map and Scorecard. He identified an objective and supporting KPI which were important to the CEO. He elected to set a target that he knew would be red? His reasoning, “To deliver to this target I need the input from other departments. I am not getting this right now. When I present my scorecard to the CEO he will ask, “Why is it red?” I will reply, it is red now and will be next quarter and the one after that and the one after that. It will remain red until you intervene and resolve this bottleneck.” And so it was – eventually.

What this manager understood (and drilled into his own team) was that a scorecard is about performance improvement – not simply delivering a green score. Alas, such mature (or should I say brave) thinking is something of a rarity. So how to resolve this. A powerful way to do this is through leveraging the concept of strategic themes which, if applied correctly, should lead to departments and functions working better together.

The value of strategic themes

As Dr. David Norton (co-creator of the Balanced Scorecard system) explained to me, “Strategy is horizontal in nature and not vertical. Strategy is about delivering solutions to common challenges that the organization is facing and this is at odds with a vertical structure.

“This is why a Strategy Map, and in particular, strategic themes are powerful…By identifying and laying out strategic themes on a map…organizations are able to overlay a horizontal form of management onto the necessary hierarchical structure. The themes enable the organizations to more effectively drive and manage cross- and intra-organizational teamwork and pursuit of common goals.”

Strategy is about delivering solutions to common challenges that the organization is facing and this is at odds with a vertical structure.

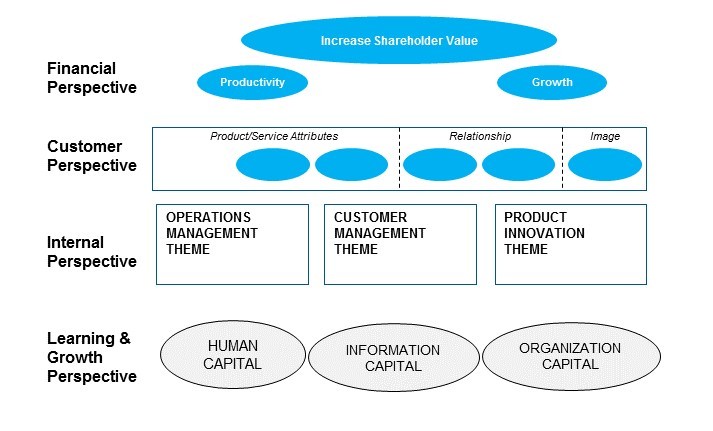

Typically, themes are introduced within the internal process perspective (where work gets done, Figure 1), although other variations cross multiple themes. Theme’s open up the possibility of creating a new accountability structure for executing strategy.

Led by a senior manager (and this should be from the executive committee level) Theme Teams (comprising individual objective “owners” and others) provide collective accountability and feedback on the performance to that theme. Theme Team meetings focus on how the component objectives work together in delivering the outcomes on the Strategy Map. Theme teams should have responsibility for choosing the strategic initiatives that deliver to the relevant objectives.

From incremental to dramatic performance improvement

In my co-authored book, Doing More with Less, the US-based consultant Bill Barberg made the useful observation that Theme Teams often look for opportunities to “trade up,” from less valuable efforts to ones that are deemed more strategically valuable: “rather than seeking funding for functional or unit-specific projects and resources that might lead to incremental improvements, they identify interventions that will dramatically improve performance to a theme – that will inevitably be cross-cutting.”

He continues, “The mindset should, hopefully, allow people to feel less need to defend their functional projects and resources.”

Banking case example

Palladium Hall of Fame inductee KiwiBank provides this illustration of the value of strategic themes in better assigning accountability. When first introducing the scorecard in about 2008, an early learning was that assigning accountability to “objective owners” simply perpetuated an already problematic silo mentality. As a result, the organization created cross-functional theme teams structured around the four themes of: Excellence in Business Processes, Sales and Service Leadership, sustainable growth and, interestingly, Learning & Growth (see below).

…an early learning was that assigning accountability to “objective owners,” simply perpetuated an already problematic silo mentality

Every executive officer was assigned to at least one enterprise-level team. About 150 employees (17 per cent of the staff) were enlisted as team members, business unit strategy leads, objective champions and measurement leads. In this way, all the work was orchestrated by the Theme Owner and although responsibilities and reporting structures were still in place, the focus was on collective accountability and high-quality performance conversations, rather than silo-based objective management. (1)

Learning and growth as a theme

Note that KiwiBank had Learning & Growth as a theme, as well as a perspective. This is not uncommon, from my experience. This theme/perspective focuses on the human, information and organization capital required to deliver the strategic processes. Collectively enabling strategic readiness, these capital components impact all the other themes and so a Learning & Growth Theme representative should attend the other theme meetings. As much as anything, this demonstrates the critical importance of people, technology, culture, etc., in delivering ultimate success (see Figure 2).

Parting words

But a word of caution. Organizations need to be careful that the themes don’t simply become a replacement for the conventional narrow silo-based management approach, with theme owners fighting with each other for the lion’s share of resources. For this reason, within the periodic review of strategy, the CEO must take care to orchestrate how the themes work together to optimize overall organizational performance.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Reference

1. Strategy Execution Champions: The Palladium Hall of Fame Report, Harvard Business School Publishing/Palladium, 2011.

Comments

No comments currently.