Continuous improvement 101: The Deming Cycle (PDCA)

“Continuous Improvement” is a term management consulting firms love using. It’s also a driving principle behind Lean Management. So, how can we achieve Continuous Improvement in our organization?

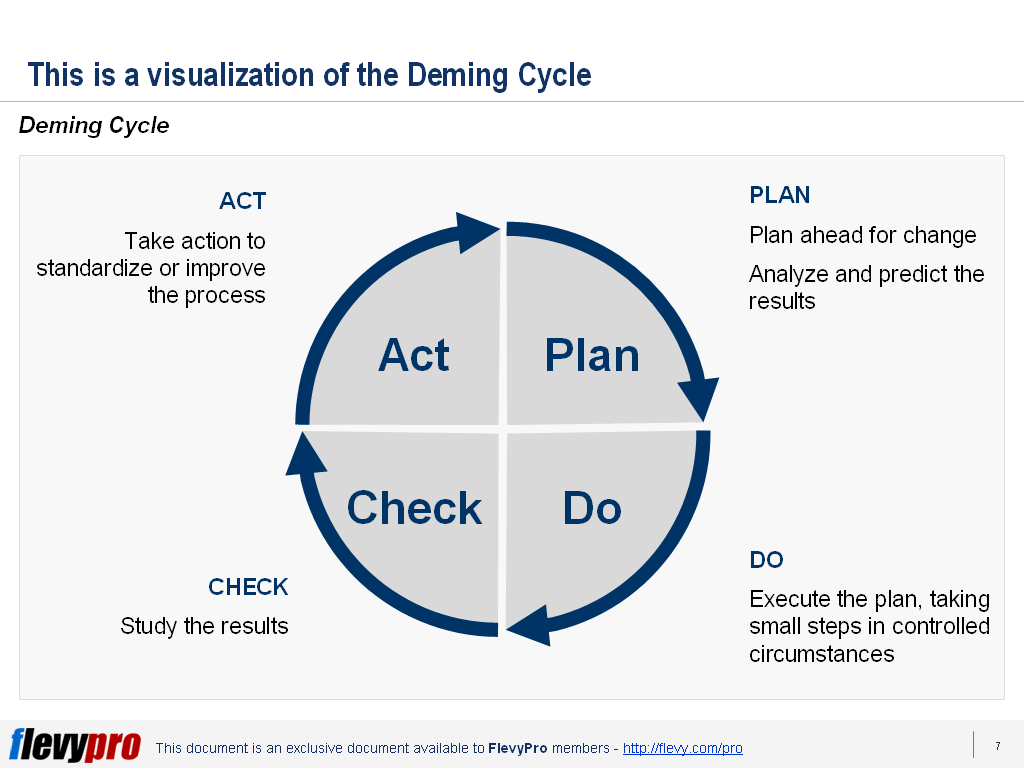

One of the most common Lean frameworks for Continuous Improvement (of quality) is the Deming Cycle – also commonly known as the PDCA Cycle, Deming Wheel, Shewhart Cycle, or Continuous Improvement Spiral. The Deming Cycle consists of a logical sequence of four repetitive steps for continuous improvement and learning: PLAN, DO, CHECK (STUDY), and ACT.

It originated in the 1920s with statistics expert Mr. Walter A. Shewhart, who introduced the concept of Plan, Do and See. Deming modified the cycle of Shewart towards: PLAN, DO, CHECK, and ACT. The Deming Cycle is related to Kaizen thinking and Just-in-Time (JIT) manufacturing. The concept of PDCA is based on the Scientific Method (which can be written as Hypothesis-Experiment-Evaluation-Do-Check), developed by Francis Bacon.

There is another version of this PDCA cycle – OPDCA. The added “O” stands for observation or as some versions say “Grasp the current condition.” This emphasis on observation and current condition has currency with Lean manufacturing/Toyota Production System literature.

There are numerous benefits to the Deming Cycle, spanning a variety of corporate functional areas. These include, but are not limited to:

- Daily routine management for the individual and/or the team

- The problem-solving process

- Project management

- Continuous development

- Vendor development

- Human resources development

- New product development

- Process trials

Here’s an overview of each of the 4 PDCA phases.

1. PLAN

This initial phase involves identifying a goal or purpose, formulating a theory, defining success metrics, and putting a plan into action. In this stage, we establish the objectives and processes necessary to deliver results per the expected output. By establishing output expectations, the completeness and accuracy of the specification is also a part of the targeted improvement.

2. DO

In the DO phase, the components of the plan are implemented (e.g. making a product). The focus is to implement the plan, execute the process, and ultimately make the product.

3. CHECK

Now, we study the actual results (measured and collected in DO) and compare against the expected results (targets or goals from the PLAN) to determine any differences. We look for deviations in implementation from the plan and also look for the appropriateness and completeness of the plan to enable the execution – i.e., “Do.”

4. ACT

If the CHECK shows that the PLAN that was implemented in DO is an improvement to the prior standard (baseline), then that becomes the new standard (baseline) for how the organization should ACT going forward (new standards are enACTed).

If the CHECK shows that the PLAN that was implemented in DO is not an improvement, then the existing standard (baseline) will remain in place.

In either case, if the CHECK showed something different than expected (whether better or worse), then there is some more learning to be done.

Note that the Deming Cycle is an iterative process, so after ACT, we return to PLAN. Over time, we will achieve Continuous Improvement in quality. Each time we renew the cycle, our organization is at a higher point of quality. Executing the cycle again will extend our knowledge further.

Excellent article Thanks! Unfortunately it is easier said than done. Track record confirms that.

Why do you think after so many years still people keep missing something critical and keep doing something wrong when deploying Deming Cycle? I am interested. Thanks i advance. I look forward to learning from you

One could theorize the PDCA model is not carried out and used to its full potential. The model is repetitive; not meant to be ran once and done. Even if major improvements are implemented using PDCA, it should be reviewed often to continue improvements. If no improvements are found (failed experiment), the baseline should remain and the results of the PDCA used (studied) in the planning phase of the next PDCA cycle. This is what results in continuous improvement.

That’s a big subject, Eduardo. Christopher has articulated some of them. Leaders don’t understand how to deploy PDSA (or most other improvement methods) because they lack the profound knowledge necessary to carry out a sustained effort. They try to use these methods for short-term cost-cutting efforts. You could even blame the western culture of accountability–it keeps our managers tied to seeing problems as things to be avoided rather than as opportunities for improvement. I have found many opportunities for improvement and been met by resentment and resistance from managers. If I find, for example, a process step that should have been removed years ago (and has caused most of the problems in the process), these managers did everything they could to either justify it or at least keep their bosses in the dark about it. They are afraid they will be held accountable for not finding it themselves. In Japan, managers proactively look for these things and are grateful for the “beginner’s eye” that can ask the crazy questions people in the process naturally seldom think to ask.

I think it’s worth mentioning that Deming did not call this PDCA. His cycle was PDSA, and he would stand and thunder “IT’S PLAN-DO-STUDY-ACT. CALL IT NOTHING ELSE!” if anyone called it PDCA within his hearing. I’m not sure how it was popularized as PDCA. He didn’t like the word “check,” as he felt the study step should be carried out with more rigor than is implied with “check.”

Nice post, David. It might be interesting to add that the bare concept itself is actually ancient and by no means a modern western invention. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301531184_Application_of_Buddhist_Teachings_in_Management_with_Focus_on_the_Deming-Cycle)

Excellent article. Thanks

Nevertheless it is easier said than done.

Why do you think after so many years still vast majority of Continuous Improvement (Deming/Juran/TQM/LSS/ TPS/Japanese/ etc. ) Platforms are wrongly deployed? I am interested. I look forward to learning from you

Hello David, Deming never embraced PDSA. He referred to it as a corruption. PDCA was a Japanese creation. It was adapted from what Deming called the Shewhart Cycle. Reference:https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=http://www.apiweb.org/circling-back.pdf&ved=0ahUKEwiciN3_897TAhVh5oMKHUeVBGIQFggkMAA&usg=AFQjCNEmKY8JuM78MW2msfMQsbxNTQuwWQ

David, You could also mention the OODA loop — Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. The one part of these loops that frequently gets too little attention is the Observe step – also in OPDCA. This is not only about observing what is changing, it is also about observing the larger whole that the continuous improvement effort is part of. I do this through the Operating Model Canvas – a high-level tool for laying out the operating model