25 year Balanced Scorecard history: The strategy-focused organization – part two

By James Creelman and Elena Gómez Domenech. Reviewed and approved by Drs Kaplan and Norton.

In part one of this series, we described the evolution of the Balanced Scorecard system from its introduction through a Harvard Business Review article in 1992 to the 1996 publication of the first book, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. You can read how this concept evolved from a measurement tool into a strategic management framework in Part 1 of this series “The First generation Balanced Scorecard“.

Here we focus on the contents of Kaplan and Norton’s second book, which introduced the five principles of the Strategy Focused Organization. In this book, Kaplan and Norton develop in detail the second part of the first book, the Balanced Scorecard, about how to manage strategy.

The Strategy Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the new Business Environment (2001)

The authors analyzed dozens of successful Balanced Scorecard users and concluded that common success factors in successful strategy implementations were the ability to achieve strategic alignment and focus.

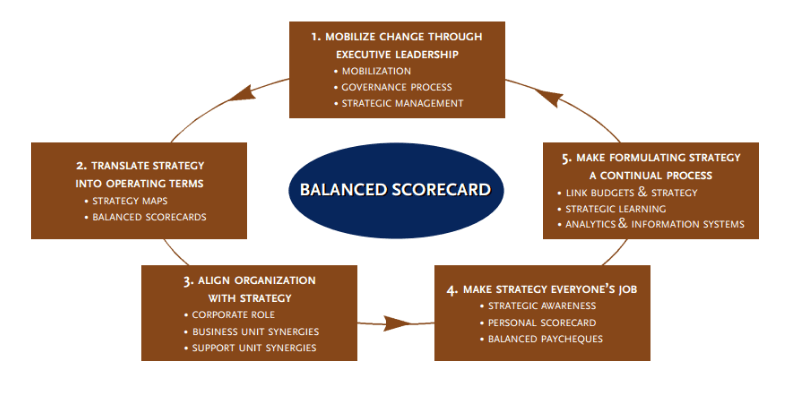

Kaplan and Norton distilled this into the five principles of the Strategy Focused Organization. Figure 1.

Principle 1: Translate strategy to operational terms

A first condition for a successful strategy implementation is being able to describe it. The authors point out that there are no widely accepted methods for doing this, unlike in the financial domain where financial plans invariably contain balance sheets or income statements. To redress this, Kaplan and Norton go one step beyond the Balanced Scorecard concept and provide a framework they called a “strategy map” which is a logical and comprehensive architecture for describing the strategy.

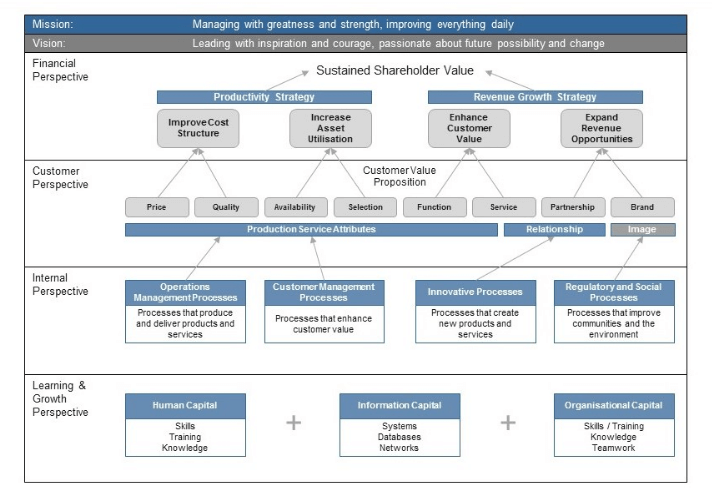

Kaplan and Norton maintain that a Balanced Scorecard should not be a mere collection of measures structured around perspectives. It should reflect the strategy of the organisation. It depicts the organisation’s strategic objectives organised into four perspectives. The Balanced Scorecard is then the set of measures, targets and initiatives that are linked to the strategy map objectives.

To understand the key to successfully delivering breakthrough performance in your organization, be sure to download a free copy of the eBook, ‘The key to Strategy Execution’ today – the perfect accompaniment to our BSC deepdive. Click here to download your copy.

The concept of the Strategy Map is explained in more detail later in their next book, dedicated to strategy maps. Figure 2.

Principle 2: Align the organization to the strategy

To make strategy happen, it is not enough to have each business unit and shared service area using their own and independent Balanced Scorecard. For maximum effectiveness, the strategies and scorecards of all such units need to be aligned and linked to each other.

Kaplan and Norton argue that strategy focused organizations can overcome the traditional silos problem that exist in most firms structured around functional units.

First, they explain how the organization (collection of divisions and business units) create synergies across their units. There are many potential areas of synergies that a corporation can create. From a financial perspective, organizations can optimize capital allocation or balance growth with risk. From a customer’s perspective, an organization can promote cross-selling and create customer focus. From an internal process standpoint, it can realize economies of scale in activities like distribution or marketing or develop value chain integration. From a learning and growth perspective, it can nurture best practice sharing and development of core competencies.

Those key value creation activities from the corporate level need to be reflected in the corporate strategy map and scorecard. Once this is done, individual business units can develop their strategies and scorecards, properly aligned and contributing to the corporate level.

Second, they develop on the synergies created through shared services. Shared services units are often created as central units because of the economies of scale and advantages of specialization that they can bring in to the organization. Typical shared service units are IT, finance, HR and procurement. A common challenge for shared services units is to be truly responsive to the business units needs and demonstrate how they create competitive advantage for their parent corporation. Kaplan and Norton illustrate through different examples how the Balanced Scorecard has proven powerful in linking and aligning shared service units with business units and corporate strategies.

Alignment is a key concept within the Kaplan and Norton strategy management framework and their 2006 book is dedicated to this key matter.

Principle 3: Make strategy everyone’s everyday job

As introduced in the Balanced Scorecard first book, Kaplan and Norton explain that successful strategy implementation requires all employees to be aligned to the strategy. Unlike in the industrial era, where most jobs were designed to be essentially straightforward and repetitive, much of the work done in the 21st century is knowledge-based. As the authors state, “ultimately, the employees are the ones who will implement the strategy”. So, employees need to understand the strategic priorities for them to be able to effectively contribute and align to them.

Kaplan and Norton differentiate three processes that strategy focused organizations use to align employees to the strategy:

- Communication and education. Strategy has to be properly communicated across the enterprise as a precondition to its effective execution. People need to be aware and understand what they will be asked to contribute to and implement. Kaplan and Norton propose that organizations set up a strategic communication program which covers several objectives: create understanding of the strategy at all levels; develop buy-in to support the strategy implementation efforts; educate the organization about the key Balanced Scorecard concepts and new way of managing the strategy; provide regular feedback on implementation. The communication actions to achieve those goals can include all kinds of media and channels.

- Development of personal and team objectives. A recommended mechanism for creating strategic alignment is to develop personal and team goals aligned to the organization’s objectives. While setting objectives for individuals is not a new idea – Management by Objectives (MBO) was created several decades earlier – the approach of the Balanced Scorecard is substantially different. With the traditional MBO model, objectives are usually relative to an “isolated”, specific unit/area, and they are short-term, tactical and financial. If the starting point is a Balanced Scorecard, objectives are derived from individuals or teams’ contribution to the strategic objectives of the organization, and therefore longer-term, strategic and oftentimes cross-functional. The authors then describe very different methods to build personal and team objectives based on company or business unit scorecards, based on real cases of different organizations.

- Incentives and reward systems (the balanced paycheque). Tying incentives and rewards programs to the Balanced Scorecard is a critical step to achieving alignment between strategy and the day-to-day operations. The authors explain different ways to do it and highlight the main considerations to design a proper compensation system linked to the scorecard. The general recommendation is not to rush into this link. In the early stages of a Balanced Scorecard implementation, organizations may lack reliable data for many measures, or may not be confident that all measures are the right ones. If an organization gets what it pays its employees to deliver, they’d better be sure of what they reward.

More organizations than ever are failing to close the gap between strategy and operational activity, with a lack of alignment and community over delivering strategic success. What is the cost in real terms? Click here to view an ROI of Strategy Execution infographic.

Principle 4: Make strategy a continual process

Most organizations have budget-based processes to control operations. Very often, the budgeting process is performed without any contact with the strategic planning process.

The authors explain that strategy focused organizations use a double-loop process which leverages on the existing management of budget and operations and integrates those with the management of the strategy. The integration among the worlds of budget/ operations and strategic management is performed through the following mechanisms:

– Linking strategy and budgeting. The question is not about choosing between strategy and budget, both elements are essential to successfully achieve the targeted results. Budgets are designed to manage tactics and day-to-day operations. Strategy focused organizations aim to link strategy to operations so Kaplan and Norton depict a 4-steps process to establish that linkage. Figure 3.

Steps 2 and 3 are the core of this process. Both (i) stretch targets set on the Balanced Scorecard measures and (ii) the resources demanded by the strategic initiatives, needed to close the performance gaps and achieve the targets, provide critical inputs to an annual budget better linked to the strategy.

A budget developed with this approach comprises two main sub-components: operational and strategic budget. The operational budget makes the bulk of the budget, as it specifies the expenses required to run the business based on the projected revenues and business activity. The strategic budget secures discretionary, additional funding and resources required to launch strategic initiatives that should close large performance gaps, as defined by the stretch targets set on (certain) Balanced Scorecard measures.

– Reporting on the strategy implementation and test, learn and adapt. Strategy implementation needs to be regularly monitored. Kaplan and Norton propose that the Balanced Scorecard becomes the agenda of a new kind of strategy review meeting where executives act as a team and work together to identify problems, assess changes in the environment and detect new opportunities that may appear during the time horizon of the strategic plan.

Principle 5: Mobilize change through executive leadership

Balanced Scorecard projects are especially powerful for leading large transformations derived from challenging strategies. For driving continuous improvement and small-scale changes, other management systems and tools do not suffice.

Mobilizing the organization for a large transformation is usually a difficult task. Kaplan and Norton reveal the importance of leaders identifying and communicating a strong case for change. Foundations for the case for change are varied. It can be a poor organizational performance, an inspiring but challenging future which will require a large cross-enterprise effort or a complex environment which forces the organization to change to stay competitive.

Kaplan and Norton observe that “the Balanced Scorecard works best when used to communicate vision and strategy, not to control the actions of subordinates”. So a Balanced Scorecard implementation is more likely to succeed when the top executives show a communicative and participative leadership style.

After the explanation of the five principles of the strategy focused organization, Kaplan and Norton include a useful chapter about common pitfalls when implementing a Balanced Scorecard project. What they called “process issues” are the most frequent and include factors such as lack of top management sponsorship and commitment, keeping the scorecard at the top level (when it is ought to be shared across the organization), considering the Balanced Scorecard a technology project, or treating it as a one-time event, when it should be a continuous management process.

To gauge your ability to successfully use a BSC to deliver your strategic initiatives, try StratexAssess, the free strategy deployment survey, designed to help you target areas of weakness in your strategy engine. Click here to start your assessment.

Parting words

In part three of this series, we describe the Strategy Map which, missing from the first book and introduced in the second, would become the most powerful element of the Balanced Scorecard system.

Comments

No comments currently.