How to control engagement overload

Lean basic control 3: how to control engagement overload

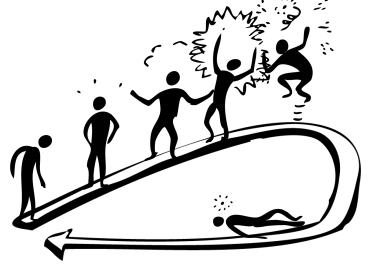

Striving for higher and higher engagement is perceived as a breakthrough mechanism that only can win, fighting the resistance to change. But what if we are running into a dead-end? Is there something like a point of no return? This discussion note focuses upon the idea that maybe the point of no return is a moment in which the organization is still in higher spheres, acting upon alarm signals as resistance to change indications.

Do you recognize:

• The best people are overdoing and risking burnout?

• Teams are only chased, going faster and faster – who is moderating?

• Some people ask: can we keep running like this? (at the coffee machine)

• The program is too good to be true!

When talking to an engineer in the workplace, I got into a vivid conversation. This is surprising since she first explains she can only have a quick chat because it is so busy. Asking questions about the causes of her daily obstacles, suddenly she has more time. It results in an hour, and it is me to end the conversation. When expressing their concerns, the primary work does not get the blame. The secondary workload, imposed by staff areas gets the blame instead.

The engineer feels it worthwhile to spend a full hour talking to a relative stranger? These type of experiences triggered me to write this discussion note, trying to understand what’s going on, but also to find ways for dealing with the underlying issues.

Per company and per area, the type of feedback are different. But, the wrap up of all stories develops the picture of a spiral model, in which employees are driven to the highest possible productivity. Also, the drive seems not to be balanced, eventually resulting in the best people being at risk of burnout symptoms or at least being forced by their families to moderate their engagement.

People at the bottom of the spiral just do their work as told. Solid, but without passion. Sometimes the conversations touch the home situation. Maybe they manage a full amateur football club. Or organize the sending of second-hand clothing to war areas? During the working day, that is where their thoughts are and where their pride is.

People at the bottom of the spiral just do their work as told. Solid, but without passion. Sometimes the conversations touch the home situation. Maybe they manage a full amateur football club. Or organize the sending of second-hand clothing to war areas? During the working day, that is where their thoughts are and where their pride is.

Next level, people enjoy their work, contributing to birthday parties at work. And developing good working relations with internal clients and internal suppliers. Ambition may be present, but rather focusing on career moves than developing in their present function (which seems cast in stone).

Next level, people enjoy their work, contributing to birthday parties at work. And developing good working relations with internal clients and internal suppliers. Ambition may be present, but rather focusing on career moves than developing in their present function (which seems cast in stone).

Nominal level engagement is the situation that we would have called “excellent” some years ago. The employees are loyal to the company, help colleagues, and take part in improvement initiatives. It is clear, however, that we are not yet at the maximum levels.

A burning platform and passionate employees will drive improvement efforts to a higher level. Winners are recognized. Maybe even the employees of the previous level are not visible anymore?

A burning platform and passionate employees will drive improvement efforts to a higher level. Winners are recognized. Maybe even the employees of the previous level are not visible anymore?

The result of a burning platform level can be that criticism is not freely shared anymore. Especially when the staff areas are competing for attention. The basis of Lean management is the focus upon the primary process. But would we overlook the daily work of routine tasks? Employees can work overstretched for a year or so, but that will be unsustainable in the long run? It is tempting for the management to proceed on the ambitious path of productivity. If competition is fierce, that may take away the last prudence.

With the promise of even higher performance yet, the program is given a boost, probably new external support is invited? People are thrilled (and maybe even hypnotized). The improvement powers are at new heights, it seems too good to be true. This time, we have a difficulty. Like an Olympic athlete cannot step back to amateur sports. We developed into an area of uncontrolled, thrilling enthusiasm from which there is no way back.

With the promise of even higher performance yet, the program is given a boost, probably new external support is invited? People are thrilled (and maybe even hypnotized). The improvement powers are at new heights, it seems too good to be true. This time, we have a difficulty. Like an Olympic athlete cannot step back to amateur sports. We developed into an area of uncontrolled, thrilling enthusiasm from which there is no way back.

For individual employees, this may have a huge impact. Stepping back from ambition and career perspective or even burnout with longer sick leave.

For the organization as a whole, it is even worse. When the best-performing people are dropping out, the examples will have a demotivating impact. Not only a few people drop out, but the energized bubble will break. If capacity in the meantime has been balanced for this level of energy, there must be a fallback incapacity, and employees were even more stretched than before.

Let us analyze what we described: the organization reached a level of thrilling energy, that cannot be sustained. But the people in the bubble could not control their run for the top performance. Whom would we expect to pull the brakes, and when do we need the braking action?

It is my opinion that the frontline leaders are the only employees in the right position to recognize the situation for their teams and their individual team members. The reason is, that above the level of frontline leaders, staff functions are competing for the limited time and energy of the shop floor.

The key is to give a mandate to the frontline leaders for intervention on the workload. That is not easy since the judgement of colleagues on “not being supportive” or on “lack of can-do mentality” will be a strong restraining force. For this control loop, the mandate must be stronger than the tribal forces present at this level of organization. Top management needs to give the “stop the work” mandate like JIDOKA does for the production line. For capacity, that is more difficult to do, when to pull the brake? In the first week overwork? After the second week in succession? Nevertheless, the frontline leader should know exactly where the performance will crack, and he must break when maybe the employees are still thrilled.

Pushed harder and reproached with resistance to change, frontline leaders could be silenced. The mandate of MT, however, will empower frontline leaders to take the key role in program management:

JIDOKA, the undervalued lean tool

“Stop the line” when any defect is seen by any worker. Western Management could for a long time not grasp this lean management instruction at Toyota. Of course, defects should be taken seriously, but stop total production? That cannot be efficient?

Yet, this was meant indeed; and maybe some stops will happen. But the impact is huge, giving priority and visibility to zero-defect production, the line will rarely be stopped.

Organizational JIDOKA?

Needed for enforcing policies, like work-life balance, like safety, like ethics, and so on. If the “stop the program” mandate is not given, all these programs will be a dead letter without meaning. The frontline leader especially must receive this mandate. Ensure sustainability.

Comments

No comments currently.